Rehabilitation / Atsui Mizu (means “Hot Water” )

■ Download Release on Bandcamp – ¥200 currently about $1.38 USD.

■Music Video

We can’t claim to replicate authentic Amapiano. Still, we wanted to infuse it with the scent and sound of our own roots. This is the story of the creation of this track—praying through chorus, shouting through guitar, and offering thanksgiving with Kavalan whisky.

I believe that was my first real experience with Amapiano. It wasn’t curiosity about the genre—it was this: how could my whole body move even with barely any kick? First came the surprise.

Listening closely, I sensed earthy bass, a bittersweet blend of sorrow and celebration. Late one night in my room, this unexpected sound quietly grabbed my heart.

Afterward, I listened to various Amapiano tracks and remixes, both domestic and international—but I was especially drawn to those with weak or almost no kick. Music that doesn’t hit you, but invites you to move within the spaces. This paradox of “making you dance by not making it dance” completely gripped me.

When people imagine dance music, they often think of strong beats and flashy groove. But what I wanted wasn’t music that makes you dance—it was a space that makes you sway. No overwhelming accents anywhere, and yet somehow the mind and body start to quiver. A sensation where silence between sounds seems to shake time itself.

Maybe in my younger days I wouldn’t have understood this sensation. It’s only with age—and seeking subtlety over strength in expression—that the essence of this music could permeate me.

That’s why I wanted to try Amapiano. Not because it’s trending, or to be praised—but as a way to convey the weight of the time I’ve walked through, and the ember still glowing within me, without hitting too hard.

Working with Prestige Kato on Amapiano

When I decided to create in this genre, the first person I consulted was my longtime partner, Prestige Kato.

He’s a passionate fan of LE SSERAFIM, especially their track “Smart,” which incorporates Amapiano—marking to him that this sound had arrived at the forefront of global pop. He agreed more quickly than I expected, and the project officially got underway.

In retrospect, this may be the first time we’ve plunged into a globally fresh genre with such specific cultural roots. We’ve experimented before, but never with something so culturally and geographically grounded like Amapiano.

And we don’t need to replicate it authentically. That wouldn’t suit us: we’re neither from South Africa, nor twenty-something clubbers. We’re people who once stepped away and quietly returned. If we simply traced Amapiano, our souls wouldn’t enter it. What was necessary, I think, was to reflect ourselves through Amapiano.

Sad yet danceable. Not loud, yet seeping in slowly. We set our course firmly: to dissolve our ages, our temperature, our rhythms of life into this music.

The final sound isn’t real Amapiano. But I do believe it’s our own Amapiano—something that could only be born where we live.

Chorus and Vocals

When we began, we agreed: “don’t overfill with sound.” We wanted to pursue our own ideal of Amapiano?“few sounds, deeply swaying.”

But that choice meant we needed something else to fill the space. We chose voices?one of the most human means.

Three or four harmonies: sometimes unison to build core, sometimes slight dissonance to cloud the air. I wondered, “How does this tiny shift affect listeners’ breath?” And layered chorus lines accordingly.

We weren’t afraid of monotony in dynamics. If monotony can bring comfort and depth, we understood?and aimed consciously to let that “stillness” float.

When younger, I prioritized vocal ability and volume and often felt envy. But with time, I’ve come to think of voice as the quality of resonance?it’s not the sound itself, but how it lingers in space. Like a lingering scent, gradually rippling within the listener.

In this track, I believe I wanted to paint space with that very “resonance.” And it’s not just technical?it’s a way of life.

Stacking voices felt like “people leaning on each other.” Not loudly resonating, just calmly standing side by side, shaking the same air. That’s the kind of time I wanted flowing beneath this song.

Meeting Em Toshiro and the Unplanned Lead Vocal

When the basic version was finished, I felt two male voices alone couldn’t reach some realms. Something was missing. There was density, but no lift?like pouring water into a stiff glass: transparent but not expansive.

It wasn’t just that a female voice was needed – it was that “another texture” was needed. A voice whose resonance before meaning shifts the landscape.

That’s when I thought of Em Toshiro. In past conversations, I had admired the beauty in her “sway” and “spaces.” I was certain that if she joined, the track would deepen.

Originally I imagined a duet – our song with her added. But once recording began, the assumption shattered.

Her voice slid into the spaces, and before I knew it, she had taken the lead melody. Not stolen, but entrusted.

I can’t say I felt no surprise at losing the lead – yet I also felt it must be the right transformation. This song isn’t about competing for the lead. Her voice was needed as gravity for this track.

Music’s essence often lives in unconscious shifts of who leads and unplanned beauty more than in balanced reasoning. This was exactly such a case.

With her voice central, the song became a single narrative?it felt less like a duet and more like her voice unifying our prayer.

Ultimately it was correct, and more than that – it felt absolutely necessary for the track.

The Climax

Toward the end – what we call the climax – I felt compelled to add one more element – not a flashy modulation, but a humble shift: a softly wavering voice from a place separate from the main vocal.

When considering who might handle this obbligato, Prestige Kato naturally came to mind. His voice has a mysterious power without being too assertive – yet occasionally shows a subtle will. I felt that balance was needed at this song’s end.

He sang almost along with the piano, but with tiny shifts in melody and timing – creating fine tremors at note edges, building a relationship that intersects yet doesn’t blend. It was a delicate obbligato performance.

Kato didn’t treat it as difficult – just accepted it intuitively. That’s his musician’s instinct – and the part I trust most.

When I listened to the full mix, I heard his obbligato not enthralling the melody, nor opposing it – but as a voice from another life. That part is something I really like.

Ultimately, music is the art of permitting multiple voices to coexist without merging – or making a story out of the fact they did not merge.

In the climax, Kato’s voice symbolizes this: a voice that speaks from outside the melody. Even if unheard, its presence is proof that it existed.

On Each Part

Log Drum ≒ Bass

In Amapiano, the log drum relates to the whole track like gravity to the horizon – one exists because of the other. But during production, I had doubts: from sound design to timing, I constantly questioned, “Is this right?”

The more I tried to be faithful to Amapiano grammar, the more I sensed, “This sound didn’t come from my life.” If I ignored that and pressed on, the track would become mere imitation.

So I resolved to leave roughness. In the end, the log drum settled into a natural presence – not demanding attention, but supporting the music quietly, like an unacknowledged skeleton.

Until the final mix, I still wasn’t confident. In youth, I might have called my uncertainty a “failure” and made stronger sounds. But now, there’s a reality only uncertainty-chosen sounds can hold.

Percussion

“To create a track that sways the body without relying on kick.”

In other words – a paradoxical challenge: to step away from the core of dance music.

In clubs and mainstream tracks, kick bass often drives the rhythm. To make people dance, I learned, requires weight and pressure. But this time, I felt the opposite.

To sway within lightness. To have people find rhythm in silence. That’s what I wanted.

We stripped away kick to the absolute minimum and filled with percussion instead. Centered on log drum, but also bongo, conga, timbales – some might not be typical for Amapiano, but I chose based on what I wanted to hear.

I sifted through libraries and samples, allowed slight quantize shifts – not precise machines, but human-like rhythm.

I may have gone too far – perhaps a smarter subtraction or refined balance could have improved it.

With time and mental bandwidth limited, though, I judged by whether I found the arrangement interesting. Fun over rightness.

Chord Progression – Challenging Banality

I’ve never been able to endure looping chords. This is almost fatal for dance music production.

I understand the beauty of repetition that builds groove and elevates pleasure through slight variation. As a listener, I deeply admire it – but once I’m the creator, I get overwhelmed wanting change. Eight measures of the same chords leave me uneasy, tempting me to add “an unexpected twist…”

This impulse came up many times in “Hot Water.” Yet this time, I restrained myself more. The overall structure is simpler than before, with chord progressions that lean a bit more obvious.

Not shaming simplicity – it’s a resolve I gained in my forties. Realizing that instead of complicating music to self-defend, approaching listeners honestly is harder, more sincere, and braver.

So I chose a familiar progression, not fearing being cliched – and challenged myself to infuse my own color within it.

At the climax, I went all the way. As if saying, “This is our irony,” I dropped in a blatant, overused progression – not as careless provocation, but as a question: Can we still feel pleasure from something so ordinary?

To believe in the familiar again. To feel warmth once more within predictability. I wanted to ask the music itself.

In the midst of the predictable, I reach for human temperature – and there lies the core essence of music.

Guitar

At first, guitar was meant to be minimal – just a couple of dry, supporting riffs to color the space and maintain warmth.

But that quiet plan quickly collapsed.

I layered spatial effects, distortion, bending, sweeping – applying techniques I had avoided. This process felt more like a ritual of mourning than music production.

When I learned of the Kavalan whisky craftsmen – how they strived under harsh conditions and poured their lives into creating “delicious” – I reflected: What have I risked for the sake of beauty? Have I honed anything? Have I sacrificed anything for a moment of “delicious”?

■reference song

The answer was embarrassingly vague. I loved music – but maybe that was all. So I channeled regret and doubt into the guitar – the blade in my hands – layer by layer.

Low D growls, harmonic fragments, slide and noise intertwined – small, shameful acts of resistance against being overlooked by the gods of music, I suppose.

I didn’t aim to show off technique. Rather, I wanted to include what I’d avoided because it was uncool. Isn’t there space for uncool sounds? With that spirit, I continued layering.

In the context of Amapiano, this guitar entry is an outright alien object. In one sense, reading the air went wrong. That’s fine. I genuinely believe that alienness brings another kind of heat to this track.

How it’s evaluated is unknown. But I’m certain that when I moved my fingers then, there was no lie in me.

Piano, Organ, Synth – Between Calm and Chaos

Where guitars poured emotion, the piano, organ, and synth sections were built with composure. Not outbursts, but architectural – working like conversing with a blueprint.

Here, subtraction was the key. In the balance, deciding when and what to play – or not – was the mission: preserve humidity and depth without being overwhelming.

But in the end, I wound up with too many tracks. The moment I hoped a sound would appear, it got swallowed. It felt paradoxical – you close off your own space while trying to create it.

A carefully composed sound disappearing into the whole – that feeling echoes middle age itself: “I did my part, but it didn’t reach.” Fading out even while existing.

Of course, I take it as the next challenge – making fewer sounds that stand out. To sharpen clarity in restraint as well as courage to play. If I can write a song where modest sounds matter until the final moment, perhaps distance from music will shrink again.

What Is “Hot Water”?

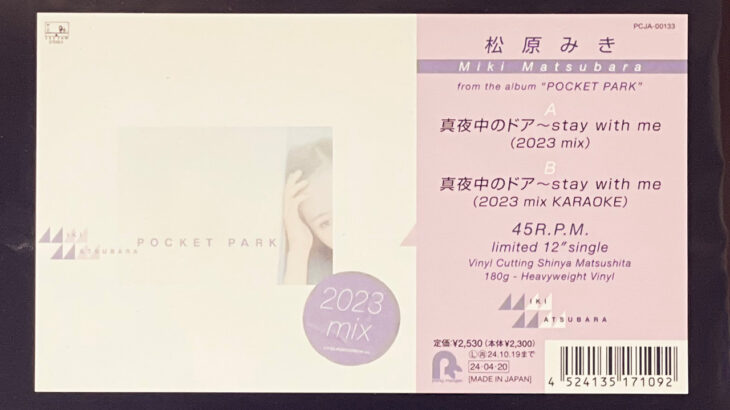

The title holds a modest tribute to the Taiwanese single-malt whisky “KAVALAN.”

Typically, whisky is associated with cool climates – misty Scotland or damp Ireland. But Kavalan defies that norm: matured in Taiwan’s subtropical heat.

High temperatures, humidity, rapid aging risks, delicately controlled processes. Yet despite – or because of – these seemingly disadvantages, it shocked the world with its quality. I saw a deep resonance with the practice of making music.

When I heard a podcast about Kavalan, it spoke of more than whisky: spirit. Liberal ideas of gender, social acceptance of true diversity, soil that allows individuals to choose how they want to be. Somehow, that aligned with the taste of the whisky.

It burns the throat. Yet beyond that pain lies a core sweetness. Like lifting beauty from the pain of living in society. When I drank it, I thought: “Could I express this in sound?” – not just because I was drunk.

Water sustains life – but “hot water” isn’t mere nourishment. It seeps into the body and scorches the heart. It takes and awakens. I earnestly wondered if I could make sound do that.

I’m aware it’s a wild wish. You can’t reproduce whisky’s depth, aroma, years, and accidental alchemy in sound resolution. But confronting that impossibility was what made this song truly ours.

Kavalan was a symbol. A record of trying to trap that “heat” – wine’s heat – inside sound, drop by drop. That’s “Hot Water.”

May this sound quietly – but surely – burn something inside you, through your ears.

コメントを書く